How to turn your OTTB into a well-rounded event horse

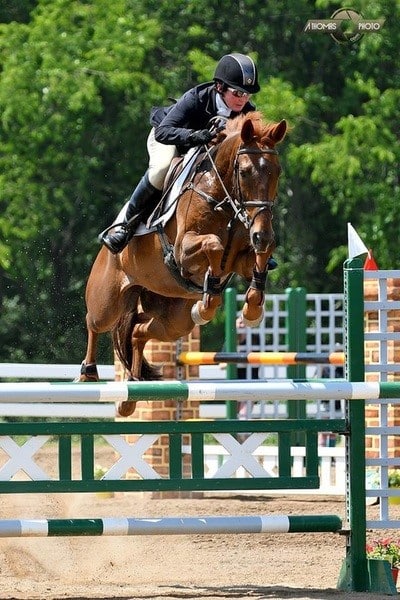

Be sure your horse is fit to do his job, but avoid overconditioning him, says Irwin, pictured here on OTTB By A Hundredth. Taylor Pence photo courtesy Hillary Irwin

To succeed in three-day eventing, you need a horse that can produce a smooth, accurate and pleasing-to-watch dressage test; be bold, forward and crafty on cross-country; and show jump quickly, cleanly and carefully — all while staying relaxed, focusing on the task at hand and responding rapidly to your correct aids. Unicorns like this do exist, of course, but they typically sell fast and for a pretty penny.

You, too, can have one of those sought-after horses that’s strong in all three phases. The catch? You must produce him yourself … or at least with a trainer’s help. And because OTTBs are well-known for their versatility across a number of disciplines, several top eventers turn to them when they’re looking for prospects.

Here’s how two of these riders find and turn their green Thoroughbreds into well-rounded successful competitors.

From the Start: Pick a Prospect

Thoroughbred Makeover veteran and eventing professional Hillary Irwin, who’s based in Ocala, Florida, recommends looking for a horse with correct conformation. Minor conformation flaws might not affect soundness or suitability to compete at your desired level, but significant ones — for example, being back at the knee or too long in the pasterns, she says — could put the horse at risk for soundness issues as he climbs the levels.

Five-star eventer Sally Cousins, who splits her time between West Grove, Pennsylvania, and Aiken, South Carolina, says she looks for a horse with nice, loose gaits. She also considers temperament key, but how she prioritizes these traits depends on the horse’s intended use.

“If I’m looking for an upper-level horse, the conformation and gaits may be more important than how quiet the horse is,” she says. On the other hand, “if I’m looking for a horse for a student that would like to go novice, and they’re a little timid or have limited riding time, I would put up with less extravagant gaits for a more settled temperament.”

Likewise, Irwin says the trait she considers most important in a prospect is temperament.

“You want a horse that’s kind, sweet and interested in its job,” she says. “It doesn’t necessarily have to be a winning racehorse — that’s why we’re getting them — but I do think you need a horse that enjoys his life.”

Hack, Take Field Trips and Hang Out

Cousins and Irwin agree that the first step to producing a well-rounded eventer is starting slow.

“I think it’s so important when you get a horse off the track that you work hard to get its body in good shape for its next career,” Cousins says. “I have found that this can take up to and sometimes past a year.”

From allowing time for any injuries and/or general body soreness to heal to helping horses gain weight if they need it, this let-down period is important to improving the horse’s physical condition.

Irwin’s 2019 Thoroughbred Makeover hopeful is a perfect example.

“He had a small tendon injury, so I did his rehab for about three months, and then he went and lived in a field with four other horses for about five months, just to be a horse,” she says.

When it’s time for your OTTB to start his second-career training, our sources’ advice remains the same: Don’t rush.

Irwin recommends starting with groundwork — and not just in the arena. She says she takes her youngsters all around her farm to do groundwork in different areas, helping hone her communication with each horse and get him used to different atmospheres and footing.

And once you’re working under saddle calmly and confidently in the arena, add frequent hacking out to your training schedule.

“I hack my horses a lot,” says Irwin. “We’ll even hack down the road (or) go to the neighbors.”

Take field trips, too.

“I think it’s very important to help the horse realize that every time it leaves the farm, it’s not going to be exciting,” Cousins says. “When we get a horse off the track, we will often, after a little bit of downtime, start taking it to different places just to see the sights while I’m schooling other horses.”

Irwin adds, “I’ll take them and sit on them while I teach a lesson or let them stand on the trailer or hand-graze. I think the more often they go off the farm and it’s no big deal, the easier they are to deal with.”

Even after her horses have progressed in their training, Irwin continues changing up the scenery and activity.

“I like them to hack (out) for 10 to 20 minutes before I ride and after,” she says. This allows them to warm up their muscles and shows them they can relax during rides, especially when they’re young.

“You want them to come out and realize their lives are easy and fun, and I think they tend to work with you a lot better,” says Irwin.

“I’m also a big fan of just letting horses hang out,” she adds. “If you have time, just sit on your horse while your friend rides or just walk around and let him eat grass.”

Keep it Short

“I don’t try to make an eventer out of a horse that does not seem to enjoy it,” says Sally Cousins, pictured here aboard her OTTB Wizard, who enjoys his job. Photo courtesy Sally Cousins

Pro tip: Don’t overwork your horse.

“I was at a Kim Severson clinic when I was a teenager, and I remember her saying, ‘If I work my horse for more than 20 minutes, it’s a really bad day,’ ” Irwin recalls. “It took me probably five years to figure out what she meant.

“You can accomplish everything you need to accomplish on the flat in 20 minutes,” she says.

Short, focused rides can help horses progress in their training without becoming overwhelmed, frustrated or sour — especially when you place them strategically between hacks as Irwin described.

“I want it to be positive — when they’re good … they get to move on,” she says. “It makes life simple.”

Also, be sure your horse is fit to do his job but avoid overconditioning him.

Generally speaking, Thoroughbreds are naturally very fit horses, Irwin says. “What your friend is doing with their Draft-cross is not going to be the same thing you’re doing with your Thoroughbred for the same level.”

That said, Cousins cautions that underconditioning horses puts them at risk for injury, and riders must learn to balance fitness, advancing training and soundness.

“If the horse is in too much work you could potentially put too many miles on its body that are not increasing its training,” she says. “I have seen more problems with horses that are not fit enough to do three phases in one day (for a horse trial). What I see is a risk to the horse’s soundness by asking it to work too hard when it’s not really fit enough to.”

Of course, this balance varies from horse to horse due to individual differences and competition level demands. For example, Irwin says her lower-level horses work five days a week.

“That’s one or two days of jumping, a day of longeing, I’ll (work them on the flat) two days, and I’ll go on hacks where I never really touch the reins,” she says. “I don’t think they need more than that, and I think it’s made the amateurs I teach feel better that they don’t feel like they need to ride their horses into the ground.”

Keep it Simple

With eventing you’re training for three different phases, yes, but don’t complicate things. Each training ride Irwin describes doesn’t just prepare your event horse for the corresponding discipline; it works synergistically with the other types of rides to prepare him for all phases.

“Your dressage is going to be the foundation for everything,” Irwin says. “I try to keep it very simple in the sense that the rules are always the same for me when I’m on the horse: They’re in front of my leg, they’re soft through their body, and they listen to their half-halts. That goes for all three phases — that’s your flatwork, that’s your show jumping, that’s your cross-country.”

She also says that regardless of whether she’s in the jumping arena or on a cross-country course, she never leaves her flatwork far behind.

“When I canter away from a jump, I might leg-yield … so I can do a 15-meter half-circle back to the same jump. I can do that in show jumping, I can do that cross-country, I can do that on the flat,” she says. And on cross-country, “we make it very simple. They do flatwork in between (schooling jumps). If they get a little wild, they do some flatwork between jumps. If they get a little slow, they go do some canters.”

Irwin adds that keeping lines of communication open with the horse is key to keeping training simple and preventing confusion.

“We always need to be subtly communicating with them,” she says, keeping our cues consistent regardless of whether we’re jumping or working on the flat.

Harness Your Strengths

Some event horses are equally gifted in all three phases. Most, however, are stronger in some than others. But you shouldn’t just accept that; your goal is to develop a well-rounded horse.

“I think it’s common for off-track Thoroughbreds to need some time to be good in the dressage and sometimes in the show jumping, as well,” Cousins says.

Be realistic, don’t expect great dressage scores the first few times out, she says, and continue working on the things that are harder for the horse at home.

“First, I think it’s always good to work with someone who is good at the weak phases,” Irwin says. Seek out a trainer or coach who’s been successful in helping horses with similar issues.

“Secondly, you have to make it fun for them,” she says. “If you make it something that’s a chore for them, they’re just going to dislike it even more.”

For instance, Irwin said her 2019 Thoroughbred Makeover hopeful isn’t the most forward horse and initially objected to leg pressure.

“So on maybe his fifth ride, I said, ‘OK, fine, we’re going to trot over some poles,’ and he thought that was great,” she says. “I tend to like getting them going on the flat a bit more before I start doing poles but, for him, it made him interested. He wants to go to the poles, and he’s going forward.”

Irwin also recommends using the horse’s existing strengths to help improve his weaknesses.

“I just started helping a lady who has a horse that’s good cross-country but gets worried in the show jumping,” she says. “So, we have to take the positive parts of the cross-country and put that into show jumping. Maybe you show jump in an open field for a while so you don’t get that claustrophobic feeling of an arena. And then remember to keep your rhythm; don’t change the rhythm just because you’re in a ring instead of a field.”

Speaking of rhythm, it’s not uncommon for OTTBs to rush jumps. After all, they were bred to run. Irwin says she’s had good luck using grids to help OTTBs keep a steady pace.

“Not necessarily 10 jumps in a row,” she says, “but setting up a ground pole between a one-stride so you help them keep the same step and (working with) canter poles on the flat. Your job is just to keep the canter the same, and their job is just to canter over the pole — it’s a very simple way to help them maintain a good canter stride, which is the key to having better show jumping.”

And, while OTTBs are known for being incredibly intelligent and getting fit quick, Irwin says, both of those traits can cause headaches for riders.

“The young ones are usually the quieter ones,” she says. “Once they learn their job and get fit, they can be a bit more of a handful before the dressage.”

In these cases she goes back to the basics and keeps things simple.

“I do lots of transitions, use circles and keep communicating with them,” she says. “Every five to eight steps, ask for something different. It doesn’t really matter what it is, just do something without overwhelming them to keep them interacting with you and not focused on the outside world.”

Finally, and importantly, Cousins adds, be sure your horse is really cut out to be an eventer. “If, after six months to a year, the horse is showing little aptitude or willingness for cross-country, it’s probably not an event horse,” she says. “I don’t try to make an eventer out of a horse that does not seem to enjoy it. I’m happy to find it a job doing the sport it prefers.”

When Things Don’t Go to Plan

Dressage is your foundation for everything in eventing. Taylor Pence photo courtesy Hillary Irwin

All horses have bad days and, at one point or another, even the most well-rounded horse can have a competition you’d like to forget. But you can still showcase at least some of his versatility.

“Make it simple,” says Irwin. “Don’t let the pressure of what everyone else is doing define what you’re doing.”

In warm-up, do exercises your horse finds easy, such as circles or leg yields, and will keep him focused on you, she adds. Take breaks. Give him time to chill.

When it’s your turn to head down center line, “plan accordingly,” Irwin says. “You usually know going into the ring that the day isn’t going how you want it to, so set yourself up for success. In a dressage test, if it says to transition at A, don’t ask for your transition at A. Ask for it five to 10 steps ahead. Make it simple. It’s better to take that pressure off and give them that extra time to react to what you’re asking.”

And remember that judges score each move in a dressage test individually. A botched transition or a less-than-submissive circle doesn’t necessarily ruin the whole test if you ride the rest of it accurately and quietly.

Carry that philosophy into the jumping phases. Maybe your normally quiet horse is feeling fresh before an early morning ride-time, or perhaps he spooked at a fence halfway around the course and can’t seem to shake it.

“Especially at the lower levels, if you need to trot, trot,” Irwin says. “If you need to walk, have a moment, pat your horse and tell him it’s OK, no one cares. They’re all looking at their phones anyway. The only one putting pressure on you is you.

“It’s not a failure if things don’t go to plan as long as the horse comes away learning something,” she adds. “If he’s having a meltdown, and you get him to not have a meltdown, you’ve already come away with a win. Just because you didn’t accomplish exactly what you wanted to accomplish that day doesn’t mean it’s not something positive.”

Final Points

While producing a well-rounded OTTB eventer, remember the three keys to success are:

1. Keeping your horse happy,

2. Keeping training simple, and

3. Getting out and about often.

“Be creative,” says Irwin. “Do anything you can to make them happy and enjoy their lives. You want to be able to keep them on a long rein and have people ask you if that’s a Thoroughbred and, when you say yes, they say, ‘Oh, he’s so quiet!’ They do want to be quiet. It’s just finding what makes them (get there).”

Adds Cousins, “Take your time. You can’t decide that a horse is a certain age and should be able to do a certain amount of work. All horses learn and grow at their own rate, and we as their riders and trainers need to recognize that.”

Eliminating the Dressage Coefficient: Helping or Hindering OTTBs?

For many years at Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) three-day events, judges scored riders as they would in normal dressage tests, and scorers calculated the percentage scores. Then scorers subtracted the percentage score from 100, multiplied the result by a coefficient of 1.5 and rounded to one decimal point. That number represented the number of penalty points the rider incurred during dressage. (For example: To calculate the score of a rider that received a 78.5% from the judges, they’d subtract 78.5 from 100 to get 21.5, the multiply that by 1.5 to arrive at a final score of 32.3.)

This scoring protocol placed more emphasis on the dressage phase (the other phases’ penalties weren’t multiplied accordingly), giving horses superior in dressage a competitive advantage over those that were stronger in the jumping phases. And in many cases horses in the latter group were Thoroughbreds.

“Obviously, there are wonderful Thoroughbreds on the flat — look at (Becky Holder’s 2008 Olympic and 2010 World Equestrian Games mount and OTTB) Courageous Comet,” says Hillary Irwin, an eventing professional from Ocala, Florida. “But they’re not all that horse.”

This often left Thoroughbreds further down the leaderboard than breeds bred for movement, with significant ground to make up to finish with top placings.

However, in 2017 the FEI Eventing Committee proposed eliminating the coefficient in hopes of placing less emphasis on the dressage phase “to promote the importance of the cross-country test, the essence of the sport.” The proposed change passed, and officials removed the coefficient from dressage scoring in 2018.

“I think that in a three-phase sport, there are certain breeds that are easier in different phases,” says five-star eventer Sally Cousins, of West Grove, Pennsylvania, and Aiken, South Carolina. “Having said that, I do think the new dressage scoring does help the Thoroughbreds.”

Irwin agrees. “I think once you get to the 3*, 4* and 5* levels, it’s probably going to help the Thoroughbreds, especially the ones that are quite careful and really special (over fences). It’ll be really interesting to see how it plays out over the next few years, but I think, overall, it will really help the Thoroughbreds.”

This article was originally published in the Spring 2019 issue of Off-Track Thoroughbred Magazine, the only publication dedicated to the Thoroughbred ex-racehorse in second careers. Want four information-packed issues a year delivered to your door or your favorite digital device? Subscribe now!