In a perfect world, every horse would end his career unblemished and perfectly sound. But because Thoroughbred racehorses are among the hardest working athletes in the equestrian world, the reality is it’s not uncommon for them to finish their careers with an injury, whether old or new. When it comes to off-track Thoroughbreds (OTTBs) retiring with recent tendon injuries, it’s a matter of determining if the injury, once healed, will affect future soundness. We spoke with two experts who helped shed some light on what to look for when you’re considering a horse with a tendon injury, how the extent and location of the injury can affect his long-term prognosis, and how you can keep these incredible athletes sound in their second careers.

Types of Tendon Injuries in Horses

Tendons are flexible, cablelike bands of tissue that attach muscle to bone. One of the most common tendon injuries you’ll find in an OTTB is a superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) tear, or a “bowed tendon.” The SDFT runs along the back of the horse’s leg. “About 8% of the horses coming into our program are retiring with a bowed tendon,” explains Danielle Montgomery, the program administrator at Pennsylvania Thoroughbred Horsemen’s Association’s Turning for Home Inc., in Bensalem. “A bow generally refers to a banana-shaped swelling along the back of the cannon bone where swelling forms in reaction to a tear to either the SDFT or the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT, which courses beneath it).” It can result from a tear or a complete rupture.

Although injuries to the flexor tendons are the most common, they are not the only tendon injuries a horse can sustain on the racetrack. Ex-racehorses can have a history of strains, tendinitis, or injuries to their extensor tendons, which run along the front of each leg. These typically result from a laceration to the front of the forelegs and are usually caused by direct trauma, such as during a fall.

“All tendon injuries are not equal,” notes Jack Root, DVM, owner of Oakhurst Equine Veterinary Services, in Newberg, Oregon. Like any injury, a tendon injury can range from mild to severe. “Depending on the type of tendon injury, some horses can be back in training in as little as six weeks. If it’s more significant it can be nine or more months until they can go back to work.”

Montgomery notes that the “perfect” bowed tendon is one with a small core lesion that’s been caught early, because core lesions are more stable than tendons torn on one side or those that have been medially displaced — moved toward the centerline of the body. In addition, these types of injuries generally respond better to treatments such as stem cells or plasma injections.

The location of the tendon injury can also affect the horse’s progress retraining for a second career. “A tear that’s right at the fetlock level isn’t going to heal as well as one that’s mid-tendon,” explains Root. “In the fetlock area, you have the tendon sheath, which surrounds the SDFT and the DDFT, as well as the distal branches of the suspensory ligament, all of which are surrounded by the annular ligament. Together these structures make up the suspensory apparatus. If the injury occurs within the tendon sheath, then you can end up with fibrous scar tissue that locks the surrounding structures together, and you lose flexibility in that area.”

If you’re seeking a horse for a career that requires full range of motion in the fetlocks, Root advises prospective owners to focus part of the prepurchase exam on ultrasound to look for any adhesions in the fetlock area.

Compared to tendon injuries lower in the leg, which typically involve more swelling and are therefore easier to identify, those further up the leg can present a diagnostic challenge. “High tendon injuries are the scary ones because they can be almost invisible if they’re behind the knee,” says Montgomery. “Even if 70% of the tendon is affected, you won’t really see (a high tendon injury) until it’s too late and you’ve already been looking into other explanations for lameness. Visually, low tendon injuries will look uglier and can involve the suspensory apparatus, which can make them trickier to heal, but either one will heal given enough time.”

One of the most common tendon injuries for an OTTB is a superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) tear, or a bowed tendon. Photos courtesy Turning From Home Inc.

Outcomes of Tendon Injuries in OTTBs

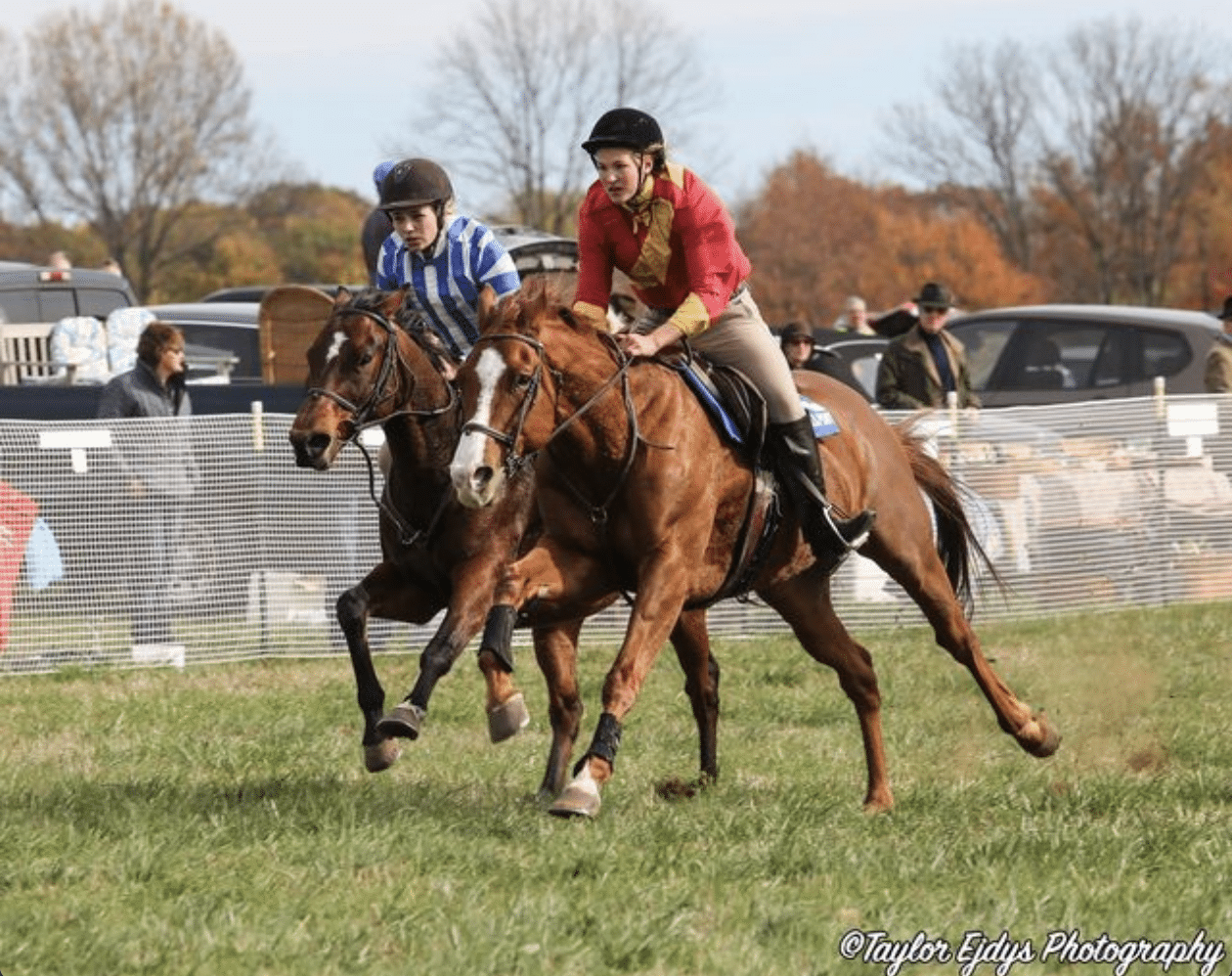

Although the structure might never appear “normal” again, even horses with a severe tendon injury can fully recover. “When I first started aftercare in 2013, there was a horse in our program scheduled to be euthanized after a full rupture to his SDFT,” says Montgomery, “but his connections wanted to give him a chance, and in 2016 he won the PA Junior Hunt Cup. The tendon was never pretty again, but his recovery was incredible and helped us rethink how we approached tendon injuries of that severity.

“For the first time in history, we are keeping files on the progress of these retired racehorses, and our veterinarians can follow their progress into their second careers,” she adds. The data coming back to Turning For Home changes how recommendations are made for new cases. “We have seen that over time, arthritis can proliferate from bone, while soft tissue often scars in and keeps getting stronger,” she continues. “There is no crystal ball, but information so readily available only helps veterinarians make more informed decisions.”

If the rest of the structures in the leg are intact and unharmed, Montgomery has found that many OTTBs with flexor tendon injuries can go on to a performance career with minimal restrictions.

As for horses with extensor tendon injuries, they typically can make a full recovery in a few months with minimal medical intervention. “The extensor tendon rarely affects the horse’s gait, and it will usually only cause them to stumble while they are healing,” says Root. “Once they’ve recovered it rarely affects future performance.”

Late Starter suffered a medially displaced full rupture along the entire SDFT in October 2013. Kate Goldenberg at Safe Haven Equine, in Perkasie, Pennsylvania, rehabbed him, and three years later he won the Pennsylvania Hunt Cup. Photo Courtesy Taylor Ejdys Photography

Buying an OTTB With a Tendon Injury

If you’re considering purchasing a retired Thoroughbred racehorse with a new or old tendon injury, it’s important to consider the realities of his potential second career. Montgomery says that although horses with a previously bowed tendon are typically sound enough for careers as hunters, jumpers, and dressage horses, she cautions against high-speed sports such as barrel racing or upper-level eventing because they put the most strain on soft tissue.

The more minor the injury, however, the fewer restrictions on the horse, so there are some important steps to take during the prepurchase exam. Montgomery recommends asking for records of any ultrasound exams of the original injury so your veterinarian can gauge the severity level at its initial presentation. The practitioner should also thoroughly ultrasound the injured (or previously injured) tendon and surrounding areas to see how much, if any, scar tissue formed during the healing process and determine what kind of rehabilitation program would benefit the horse. “With a lot of tendon injuries, you can end up with bony injuries associated with them where they attach into the bones,” cautions Root. “It’s important to do a thorough exam so you can have the most accurate diagnosis possible.”

Tendon Injury Rehabilitation in Former Racehorses

If you bring home a retired racehorse with a recent tendon injury, starting with an accurate diagnosis will best equip you to help him fully recover. The healing time will depend on the severity and location of the injury. Typically, the healing process includes four to six weeks of stall rest to prevent reinjury, paired with anti-inflammatory support in the form of NSAIDs and icing, with the addition of steroidal anti-inflammatory medication on a case-by-case basis to prevent injury to the surrounding tissues and structures. Root recommends supporting the legs with standing wraps during this time to promote blood flow.

Through the duration of the stall-rest phase, Root and Montgomery both recommend hand- or tack-walking the horse twice daily for 15-20 minutes each session. “One of the biggest mistakes people make with tendon rehab is keeping the horse on strict stall rest for too long,” says Montgomery. “Since those tendon fibers all move independently of each other, if you lock a horse up in a stall, it prevents the fibers from remodeling correctly, and you’ll end up with so much scar tissue and adhesions between structures that the tendon won’t have as much flexibility.”

After that, if the horse is healing normally, he can be turned out in a paddock with firm ground.

If therapeutic modalities are available to you, Montgomery has seen success with those that promote circulation. “The number one thing we turn to is shock wave therapy since it helps increase circulation,” she says. “But we’ve also had success with laser therapy and hydrotherapy. I don’t think they’ve necessarily made the tendons heal faster, but I think they made them heal better.”

Throughout the healing process, Root recommends rechecks with your veterinarian twice a month for the first couple of months, followed by monthly appointments until the horse is cleared to slowly return to work.

Buzzwork sustained two total ruptures of both front SDFTs. His owners were told he should be euthanized, but they gave him a chance. He competed in Field Hunter and Dressage with Kate Goldenberg at the 2017 Thoroughbred Makeover. Photo Courtesy Taylor Ejdys Photography

Preventing Tendon Reinjury in OTTBs

Every horse is unique, and every injury is also unique. “Just because they bowed a tendon on the track doesn’t mean they’re going to do it again when they come home,” says Montgomery. “On the track, they can have long toes and they can overstrain tendons with speed workouts, so it’s hard to bring them back to racing, but you can change a lot once they come home.” Simply rebalancing their feet, avoiding muddy turnout, and ensuring that they aren’t overworked in soft, deep footing can reduce the likelihood of them reinjuring the area. “If they have poor conformation or have a proclivity toward injuring tendons, then they’re always going to be at risk,” she explains. “But if the injury resulted from a funny step and is properly rehabbed, then the risk of injury goes down.”

Root adds that because most major injuries start off as minor injuries, it’s best to be as attentive as possible when you have a horse with an old tendon injury. “Before and after every ride, you need to run your hands up and down the horse’s legs to check for tender, warm, or swollen areas,” he advises. “By being proactive you can prevent an old injury from returning or a new one from becoming a major problem.” Root is also a big proponent of supporting horse’s legs with standing wraps after heavy training sessions because the blood flow increase will boost the tissue’s metabolic rate and cause any injured or sore areas to heal faster.

Tendon injuries in horses take time and patience to heal. Root notes that the biggest mistake he sees with healing tendon injuries is putting the horse back into work too soon. If you give an OTTB the time he needs to make a full recovery, and are willing to be diligent with preventing re-injury, you can ultimately end up with an exceptional partner with a long, healthy second career.

Corie Traylor is a full-time writer living in Portland, Oregon. She grew up riding horses on her family’s farm and currently owns two OTTBs, Bess and Mia.