Photo by Captivation Media

Many owners are familiar with bony injuries, such as osteoarthritis or fractures. Soft tissue injuries, on the other hand, can bring a sense of ambiguity and uncertainty of the future. With rehabilitation techniques and length to recovery varying so immensely between each soft tissue injury, the unknown associated with these injuries can be a source of frustration among owners.

“Knowledge is power, and it can help you overcome any fear of the unexpected.” – Jay Shetty

While veterinarians cannot remove all fear and unexpectedness when it comes to horses, we can provide knowledge, which is a powerful tool. Understanding what is happening with your horse and why your veterinarian is recommending certain imaging modalities and rehabilitation plans, puts control back into your hands.

What Should You Look For

Becoming familiar with your horse’s normal is an important factor with soft tissue injuries. Pay attention to the normal appearance of limbs, tendons, and musculature. Pay attention to how they move when they are feeling good. By knowing your horse’s normal, it will be easier to recognize any deviations from that normal.

Acute changes to your horse’s limb can help indicate a soft tissue injury. Look for changes in the tendon profile. Are the tendons sitting flat or is there a “bow” in the tendons? Is there swelling all over the entire limb or a focal region? Is there a new swelling in a specific muscle group? If there is ever any uncertainty, comparing to the other limbs or side is a great tool. There will occasionally be bilateral issues, but often the opposite side will provide a good comparison. Changes to your horse’s gait, either on the ground or under saddle, can also clue you into an injury. Even subtle changes, such as unwillingness to pick up a lead, can be important. Appreciating these changes and sharing this information with your veterinarian allows them to have a better idea of what is happening.

The Performance Exam

When a soft tissue injury is suspected, your veterinarian will often start with a thorough palpation of the horse. During this palpation, they are feeling for any swelling, restrictions in range of motion, any heat over certain structures, or any pain on palpation. You will often see your veterinarian holding the limb and palpating each individual tendon and ligament. Doing this in an un-weighted position provides better access to each structure. Following palpation, your veterinarian will watch your horse move. This often starts with walking and trotting in a straight line. Based on the degree of lameness, they will then move to lunging or move to different surfaces, hard and soft ground. Different surfaces and motions (i.e. straight vs circling) can provide more information on the structures involved. A generalization that is often made is that soft tissue injuries appear worse on soft surfaces and bony injuries appear worse on hard ground. This generalization is made because softer surfaces allow the hoof to sink into the ground, thus putting further strain on soft tissue structures.

Flexions are often performed next to isolate which region the injury may be coming from. Flexions are not a specific test, as it is difficult to flex a single joint in the horse limb without inherently flexing another due to their anatomy, but they do provide more information. The next step is often perineural anesthesia or “nerve blocking.” This is performed with a local anesthetic, such as mepivacaine (Carbocaine) or lidocaine, to block sensation to specific regions, starting low at the foot and moving up. After the block is administered and an appropriate amount of time has passed (5-15 minutes), your veterinarian will watch your horse move with the block in place. When examining your horse following a block, we are looking for a significant change in the lameness. This does not always mean complete resolution of the lameness. You may hear your veterinarians talk in percentages, such as “the palmar digital nerve block improved the lameness 85%.” All these steps are helping your veterinarian better target their diagnostic imaging.

Diagnostic Imaging

Most owners are familiar with radiographs as a diagnostic imaging modality. While radiographs are best for looking at bones, they do have the ability to tell us basic information about soft tissue structures. For example, radiographs can highlight soft tissue thickening, mineralization within soft tissues, gas, and bony changes at the areas of soft tissue attachment (entheses). Your veterinarian may use radiographs to rule out any overt boney issues first, before moving onto more soft tissue specific modalities.

The best and most common modality to evaluate soft tissue structures in the field is ultrasonography. Ultrasound is a two-dimensional imaging technique that uses sound waves and how quickly they return to the transducer, to generate an image. The density of the structure that the sound waves move through determines how quickly the sound wave returns. For example, bone is the densest structure meaning it returns at the highest speed, resulting in a white image (hyperechoic). Fluid-filled structures propagate at medium-speeds and result in a dark image (anechoic). These sound waves return to the piezoelectric crystals in the scan head (hand-held piece placed onto the horse) and those crystals take the waves and convert to electrical energy, creating the image on the screen.

Ultrasounding a soft tissue injury is best performed approximately 1 week after the initial injury occurs. This is due to many lesions expanding during the initial days after injury. While you can ultrasound the area right after it happens, your veterinarian may suggest re-scanning several days later to determine the full extent of the injury. So, what exactly is your veterinarian looking for? They are looking for tendon or ligament fiber irregularities and lesions within the tendon or ligament themselves, such as a core-lesion. Tendons and ligaments are composed primarily of Type I collagen, therefore when there is tendon fiber disruption and subsequent inflammation, fluid and inflammatory cells infiltrate the region. This fluid, as we previously discussed, shows up dark on the ultrasound. With an acute injury, this results in dark striations or holes in the normal tendon structure. Your veterinarian is also looking at the size of the tendon or ligament. With injury, these structures tend to increase in size. Most ultrasound machines have the capability to measure these structures. You may hear your veterinarian report this as the cross-sectional area (CSA). Other aspects your veterinarian is looking for is change in the shape, location and any fluid surrounding the structures. Ultrasound can also be used to evaluate joint-associated structures, such as synovium, joint fluid quality, collateral ligaments, and menisci. Muscle injuries can also be evaluated, assessing for edema, fluid accumulation (hematoma or seroma), and any disruption in the muscle fibers indicating a tear or strain. Ultrasound is also a great modality for monitoring healing within an injury. Part of the rehabilitation process includes periodically checking the structure with the ultrasound to make sure healing is progressing appropriately.

As important of a tool ultrasonography is, it does have its limitations. Ultrasound does not have the best capability of imaging through the hoof, meaning any soft tissue injuries within the hoof capsule are difficult to visualize. Ultrasound also has the limitation of the depth it can penetrate, making injuries of the upper limb and pelvis more difficult to visualize. Since ultrasound is also a two-dimensional image, we are only imaging one aspect of the structure when it comes to the upper limb, pelvis and back.

Dr. Sarah Escaro ultrasounding a distal limb with her assistant. Photo courtesy Hagyard Equine Medical Institute

Another great imaging modality is magnetic resonance imaging or MRI. MRI is a cross-sectional (or 3D) image generated from the movement of hydrogen ions within a magnet. There is a low-field magnet and high-field magnet, measured in tesla units. High-field MRI’s require laying the horse down (general anesthesia) but produces a more detailed image. Low-field MRI’s can be performed standing, which means the horse does not need to be placed under general anesthesia, but the image detail is lower. While MRI has become the gold standard for imaging soft tissue injuries from the carpus/hock down, both low-field and high-field MRI have their advantages and disadvantages. Due to size constraints, imaging higher than the hock or carpus is difficult. Thankfully, larger bore sizes (hole the horse moves through for the image) are becoming available, allowing better imaging of the proximal limb. Another disadvantage is that MRI machines are located at referral or primary hospitals and are not mobile for the field. They also come at a higher cost, especially with the addition of general anesthesia for the high-field images. An MRI is not always a substitute for ultrasonography, but in addition to. Your veterinarian may suggest having an MRI performed after ultrasounding to gather even more information.

Now What?

Your horse has now been diagnosed with a soft tissue injury, so now what? The frustrating part of a soft tissue injury is that each injury can have a slight variation to its rehabilitation plan. They do have similarities, which we will discuss in this article. If your horse has an injury, please create and follow a specific treatment plan made by your veterinarian. This article will only discuss generalizations of soft tissue injury rehabilitation and are not a substitute for a veterinarian.

General Rehabilitation Plans – Distal Limb

I believe it’s important to briefly touch on the different phases of injury and healing. This section will specifically discuss tendon healing. The first phase in healing is the acute inflammatory phase. The amount of inflammation appreciated during this phase depends on the severity of the injury. During this time, we often see hemorrhage, edema, and release of white blood cells and proteolytic enzymes (degrades necrotic collagen). While some inflammation is good for healing, too much can cause further damage to the tissue. This is why anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), cryotherapy (cold-hosing, ice boots) and stall rest are used initially to reduce excessive inflammation. This phase usually lasts about 1-2 weeks.

The second phase of healing is the subacute reparative phase, which starts about 3 weeks following injury. During this phase, blood vessels and scar tissue are being formed. This scar tissue is composed of randomly organized type III collagen. Unfortunately, this scar tissue is weaker than the original tendon tissue (type I collagen), predisposing the area to reinjury. This is why during this phase, stall rest and restricted movement (i.e. hand walking) are strictly controlled.

The third phase of healing is the chronic remodeling phase. During this phase, the type III collagen laid down during the subacute reparative phase is slowly converted to type I collagen. This process takes several months, over which controlled exercise enhances this conversion. With enhanced conversion, there is subsequently improved mechanical tendon strength. This newly converted collagen will never have the strength of the original tendon, which is why re-injury is such a concern.

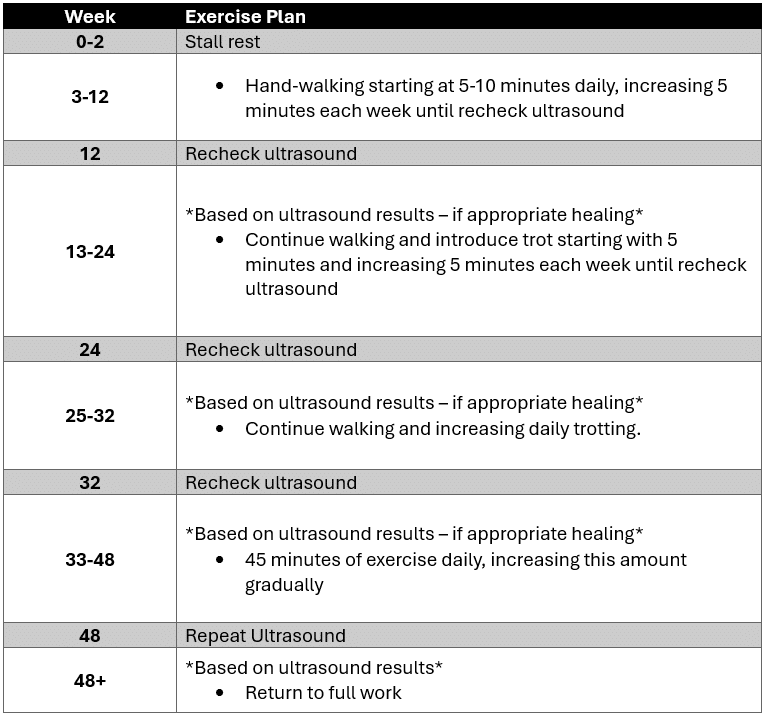

The goals with any treatment program include initially minimizing inflammation during the acute inflammation phase and enhancing regeneration and successful healing of the tendon. During this healing process, repeat ultrasound examinations are important to assess how the tendon is responding to the treatment plan. A generalized example rehabilitation plan for a tendon injury is as follows:

With the advances in diagnostic imaging and rehabilitation processes, soft tissue injuries can often have a good prognosis for return to activity. Understanding what to look for can help catch these injuries early to start implementing treatment sooner. Even with all this information, soft tissue injuries can still be daunting, but understanding what is happening can make the diagnostic and rehabilitation process easier for everyone involved. Please work with your veterinarian to create a custom plan that works for your goals and your horse.

Dr. Weinberg is originally from southeastern Ohio, raised around corn, 4-H animals, and a small-town community. She has always loved horses, but her original career path was marine biology, where she received a Bachelor’s of Science in Marine Science from Coastal Carolina University. After spending 6 months working with sea turtles at the South Carolina Aquarium, she returned to Ohio to attend veterinary school at THE Ohio State University where she fell in love with equine medicine. After graduating, Dr. Weinberg stayed at Ohio State for an equine rotating internship, where her passion for lameness and sport horses grew. This passion took her to sunny California, where she spent the last year as the Equine Integrative Sports Medicine Intern at UC Davis, working alongside boarded ACVSMR-boarded clinicians, surgeons, and skilled diagnostic imaging clinicians before joining the Hagyard team. Her interests include sports medicine for all disciplines, integrative treatment modalities, podiatry/therapeutic shoeing, and the axial skeleton.