Ponies and their riders ready to meet the field in the paddock between races. Photo by Steve Heath

Pony riders and their pony horses play key roles in horse racing. They serve as the safety net during morning training and afternoon races, guiding spirited Thoroughbreds on and off the track and helping maintain calm when things go wrong. At major racing venues like Churchill Downs, in Kentucky, and Del Mar, in California, veteran pony riders such as Torrie Ann Needham partner with their mounts to help.

The Difference Between Pony Rider and Outrider

Outriders are professional horsemen and women who maintain safety during training and racing hours. Mounted on steady horses known as pony horses, they assist in catching loose horses, lead the post parades on race day and help jockeys pull up their horses once they cross the finish line. You can easily spot them on race day because they wear red jackets. On the other hand, pony riders escort nervous or unruly horses during their morning training sessions and guide them to and from the starting gate before a race.

Needham has been a pony rider since 1977. She started out galloping horses at Hollywood Park and soon began ponying (leading horses while mounted) horses in the morning. That part-time gig evolved into a career in the saddle. “It just kind of fell into place,” she says. “I just started ponying in the mornings, and then I started ponying at the races.”

Pony riders and outriders must be quick-thinking, calm under pressure and deeply attuned to the goings on at the track. Every day presents new challenges, and their partnerships with and the personalities of their pony horses remain critical to safety.

What Makes a Good Pony Horse?

Most pony horses — also called track ponies — have quiet temperaments, steady nerves and large, sturdy builds; they also tend to be geldings. The ideal pony horse doesn’t overreact, doesn’t mind another horse leaning on him and stays level-headed when situations turn unpredictable. “They’ve got to be quiet,” says Needham. “When you’ve got a racehorse that’s high on the muscle (fit and excited), (the pony horse’s calmness) hopefully influences the racehorse.”

Although some pony horses come from stock horse backgrounds, many of them are OTTBs. Their long stride and stamina can be advantages when matching pace with a racehorse. “A Quarter Horse can’t keep up with a Thoroughbred because of their shorter stride,” Needham says. “A Thoroughbred can gallop out with a Thoroughbred racehorse easier.”

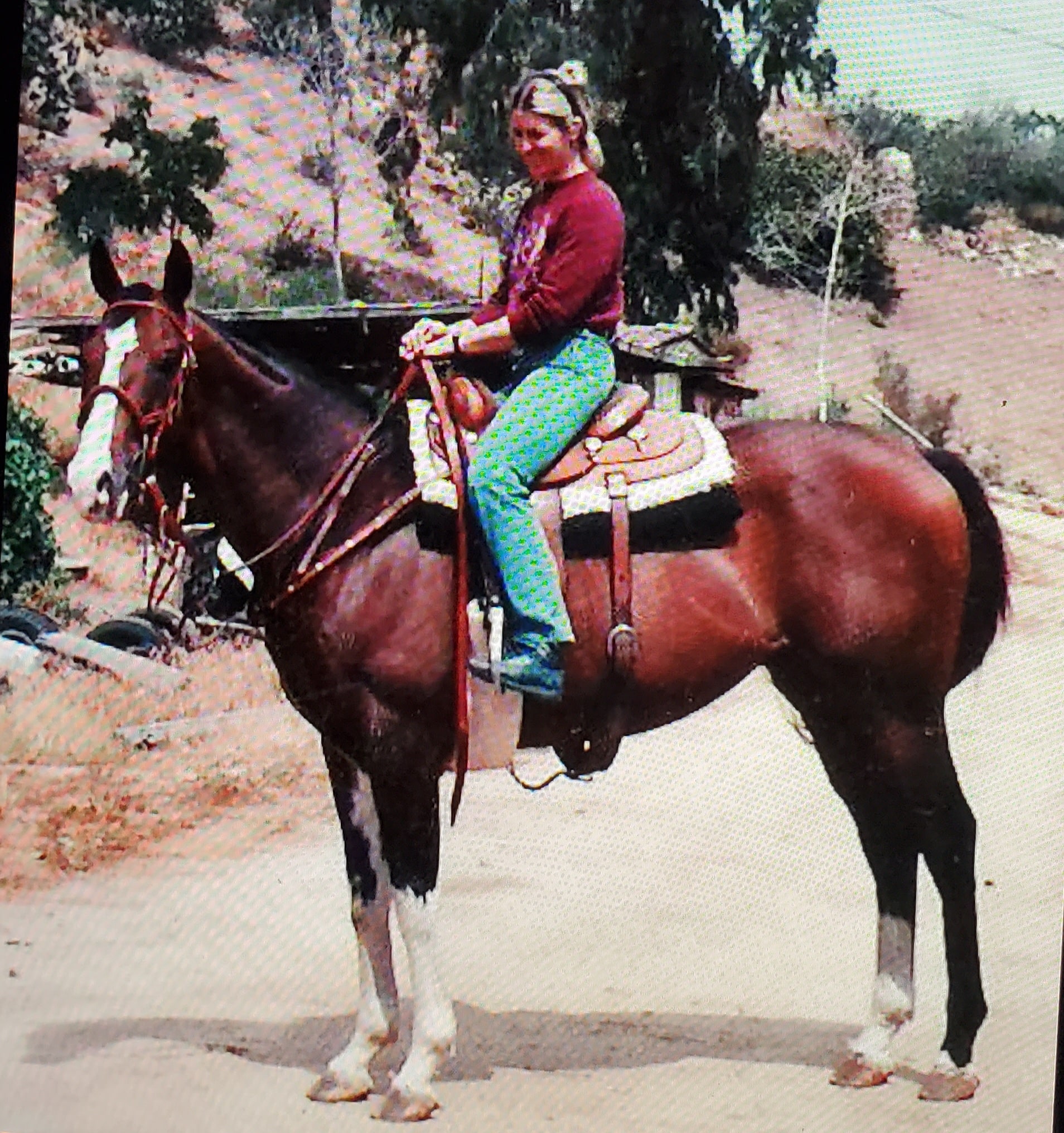

Needham says one of her all-time favorite pony horses was Joker’s Jig (Vigors — Cute n’ Pretty, Lucky Debonair) — a Thoroughbred she first met when galloping him on the track. He always stayed quiet and calm, whether he was out for a training session or in the barn, so when it came time for him to retire, she bought him. Joker went on to pony horses at major races including the Kentucky Derby and Breeders’ Cup.

Torrie Ann Needham and her beloved pony horse Joker’s Jig who passed away several years ago at the age of 28.

Photo courtesy of Torrie Ann Needham

A Day in the Life of Outriders and Pony Riders

In the mornings at the racecourse, outriders patrol the track while horses train. They help direct traffic, keep horses moving safely around the oval and catch loose horses when needed. Pony riders spend their mornings leading high-strung or inexperienced horses to help them stay focused and safe. Needham explains that a well-trained pony horse acts like an anchor for nervous Thoroughbreds. “Some just lean against the pony horse like they’re a big comfy couch,” she says.

Pony riders take on one of their most visible roles in the afternoon: following an outrider and escorting racehorses to the starting gate. They keep the horses calm and on track while spectators, loudspeakers and swirling activity add to the pressure. “The noise on the racetrack is like nothing you’ve ever heard,” she says, “which is why the pony horses have to be so calm. A pony can blow up, and then the rider will have to turn their horse loose.”

At the top levels of the sport, the racehorses usually handle the environment just fine. But in some cases, Needham says, they become overly excited because of the noise, and then they really need the support of a calm pony horse.

Sometimes pony riders intervene when a horse bolts, unseats its rider or refuses to load in the gate. That can mean galloping after a loose horse or assisting jockeys on board difficult mounts. Needham has handled countless incidents, including averting dangerous near misses thanks to quick reflexes and a solid pony partner.

How Do Pony Horses and Racehorses Interact?

As with any relationship, every pony horse/racehorse pairing is unique. Pony riders quickly learn which horses pair well together — and when to keep their distance. “They’ve all got their quirks,” Needham says. “Some racehorses don’t like certain ponies, or they’re just not comfortable with a particular match.”

She described racehorses eyeing dramatic or reactive pony horses with irritation. “They’re sitting there watching the pony like, ‘What an idiot. You’re supposed to be keeping me calm. What are you doing?’” When the pairing works, though, it creates a calm, confident atmosphere that helps the racehorse perform his best.

The Calm Behind the Scenes at Big Venues

During events like the Breeders’ Cup and Kentucky Derby, pony riders and their mounts take center stage. They escort elite racehorses during training hours and lead them to post on race day.

Needham has escorted numerous high-profile horses in her career, including two-time Horse of the Year John Henry (Ole Bob Bowers — Once Double, Double Jay), as well as Mystik Dan (Goldencents — Ma’am, Colonel John) and Thorpedo Anna (Fast Anna — Sataves, Uncle Mo), winners of the 2024 Kentucky Derby and Kentucky Oaks, respectively. Thorpedo Anna remains one of her favorites. “I’ll never forget her. She’s amazing. Doesn’t matter what track or surface — she just runs.”

Even during high-pressure moments, Needham focuses on keeping horses comfortable and calm. One morning at Del Mar, she and Thorpedo Anna took a long, quiet walk as the sun came up. “We didn’t want to get her all riled up,” she says. “We were just having a good old time.”

Ponying for a Fresh Start

People often associate ponying with the racetrack but, for professionals like Amy Silvera and Lily Santulli, it plays a far more strategic role in the retraining of OTTBs. When used thoughtfully, it can help restart a horse’s mindset, build their confidence and lay a strong foundation for future work.

Silvera, a Pennsylvania-based trainer with a background in eventing, show jumping and dressage, incorporates ponying early in her program to ease OTTBs into life beyond the track. “Up until that point racing is all they’ve known,” she explains. “Ponying helps transition them into a second career. It allows them to follow the example of a calm, seasoned horse out on trails, which can be mentally grounding.”

That exposure — especially outside an arena — gives horses a chance to start physically and mentally rebuilding. “It’s an excellent way to start working muscle groups that aren’t typically developed through race training,” she says. “They’re free to move through their bodies and begin using their backs properly.”

Silvera also uses ponying for horses rehabbing from injury, calling it “a fantastic way to rebuild topline with minimal pressure from a rider.”

Santulli, who runs Red Horse Ranch and Versatility, in Troutdale, Oregon, draws on more than 30 years of experience in foundation work and colt starting. She treats OTTBs like fresh starts and uses ponying to reinforce lessons from groundwork. “It helps teach the horse to give to pressure, get comfortable with movement above their head and learn how to regulate themselves around another horse.”

Both trainers emphasize the importance of a reliable pony horse. “It’s essential that the pony horse is tolerant of bumps, unexpected contact and the occasional lead rope in awkward places,” says Silvera.

Santulli adds, “Not all horses are cut out to pony. If your saddle horse doesn’t understand the job, don’t use them.”

Done well, ponying can be a powerful teaching tool, but both trainers agree it’s not a cure-all. “Don’t let ponying become a crutch,” says Santulli. “Use it to build confidence, not to mask problems.”

In the hands of a thoughtful horseperson, ponying becomes more than just a transitional step. This approach introduces new expectations with reassurance and lets an OTTB know he’s not figuring it out alone.

Lily Santulli ponies a young horse with her saddle horse, Red, who she claims is a better trainer than she is most of the time.

Photo courtesy of Lily Santulli.

From Flight to Freedom — Paris’ Story

Lily Santulli has worked with hundreds of young horses and restarts, but one OTTB mare named Paris left a lasting impression. “She was probably the most insecure and troubled horse I’ve ever come across,” Santulli recalls. “She would bolt, rear, kick — she hated human contact. Extremely herd-bound. Living in constant flight.”

Paris’ program began with groundwork, giving her space to learn without pressure. But a turning point came when Santulli introduced ponying about 30 days into training. “Ponying allowed me to work above her head, expose her to pressure and movement in a nonthreatening way and start to rebuild her confidence day by day,” she says.

Over time Paris began to soften — both mentally and physically. “She stopped pacing in the pasture. She let the kids brush her. Grazing became her favorite thing,” Santulli says. “She went from completely shut down to one of the funnest horses to ride.”

Paris’ transformation demonstrates how ponying can serve not only as a training tool but also to reinforce trust, connection and calm in the lives of OTTBs.